Omniscient Debugger User Manual

Omniscient debugging is the concept of debugging by retaining state changes

and "navigating" backwards in time to find the problem. The ODB is a

proof-of-concept implementation written in Java. It is neither optimized nor

integrated. None-the-less, I believe you will find it to be the most

effective debugger you have ever used.

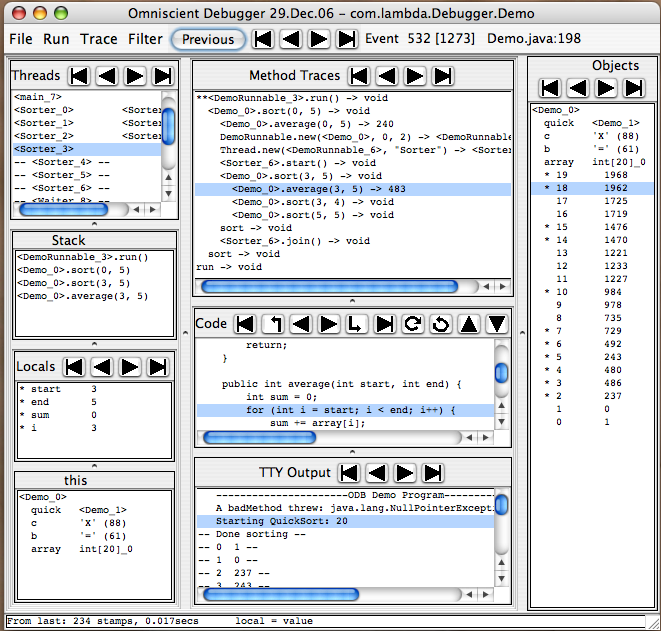

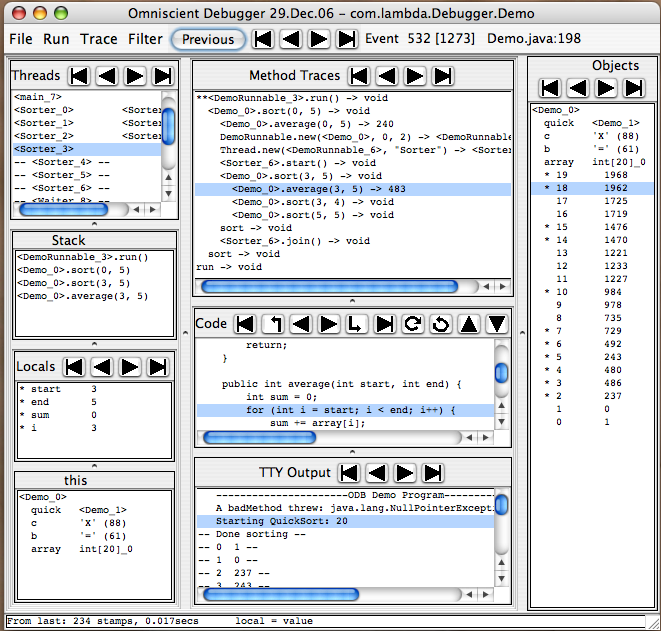

Figure 1

The ODB is based on the idea of collecting "time stamps" at each point of

interest in a program and then allowing the programmer to use those time

stamps to explore the history of that program run. "Interesting" points

include: setting a variable value (local, instance, array element, static),

making a method call, throwing/catching an exception, and creating a new

object. The debugger inserts code into the class files to collect these

stamps. (The instrumentation is done using the wonderful BCEL package which

is available from www.Jakarta.Apache.org/bcel.) When the program runs, time

stamps will be recorded.

The ODB does not require any preprocessing, or any special repository.

There are no limitations on the program being debugged. It

is not even absolutely necessary to have the source code available. After

installing (see below), the programmer runs the debugger by calling:

% debug TargetProgram arg1 arg2 arg3

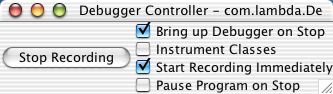

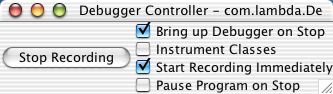

The debugger will display a little control window and start the program. The

main debugger window will pop up when the program calls exit() or when the

programmer pushes the "Stop Recording" button in the control window. The

programmer will then be able to navigate through the time stamps to find

interesting events.

Once the debugger main window is up, all recording will be turned off, even

if the program is still running. You may resume recording using the control

window.

Data Display Formats

The ODB needs a print

string, so it supplies its own format showing the class name and an index

number: <MyObject_75>, chopping off the package. You may add

an additional string to it: <MyObject_75 square> (see defaults file).

Class objects are displayed as just the class name (e.g., Person ). Boolean

values, numbers, and characters are displayed as expected: true, false,

123, 45.678, 'X' (88). Bytes are also displayed like characters

with both the ASCII character and the decimal value in parenthesis.

Long names and strings (more than 20 characters) will be elided and printed as:

<TestLongName..0> in the trace pane. In the objects pane more

room is provided (500 characters). Very long strings and large objects may be printed out to

the terminal via the menu item Objects->Print.

Method traces are displayed with the object (or class object for static methods),

followed by the method name, the first three arguments, and finally an

arrow and the return value. Methods that haven't returned just show

****. Methods that throw (or propagate) an exception show ****<Exception>.

They are indented appropriately, hence in figure 1, sort()

called average() once, new() twice, then start(), and finally sort()

recursively. The recursive call to sort()

called average(), etc.

Returns from methods are displayed on separate lines as sort -> void.

If the return line would be right after the call line, it will not be

displayed. If the program catches an exception from more than one method

call deep, the display will appear jagged because there won't be any intervening

"return lines".

Constructors will be shown like static methods (MyObject.new() -> <MyObject_1>),

as will super methods.

The Display Panes

The ODB attempts to show all the data of interest on the screen at

the same time. Popup dialogues are only used for finding source files and selecting values, which

are rarely done. The panes are all updated to display the same time

stamp.

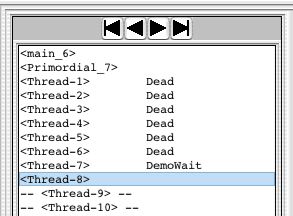

Threads Pane

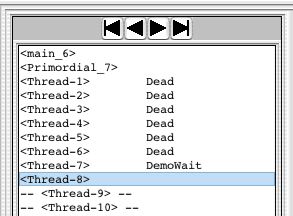

Threads are displayed in the format <Thread-3>, where "Thread-3" is

whatever is returned by getName(). If the currently selected time is

previous to the creation of the thread (before the thread's first time

stamp), it is shown as -- <Thread-3> --, and as <Thread-3> Dead if after

the thread has exited (after the last time stamp for a thread whose

isAlive() method returns false). If the thread is blocked, waiting for a

lock or in a call to wait() or join(), it is shown as <Thread-10> <MyObj_2>.

Adding the thread to the objects pane will show this as a

pseudo-instance variable _blockedOn.

Stack Pane

All methods on the stack are displayed here. Single-clicking on a line will

update the Code pane, the arguments, and the local variables for that stack

pane. The current time stamp will not be changed. Pushing any button will

act on the actual time, not what is displayed in the code pane. (It's not

clear what is most "intuitive" here.) The menu command Code->Goto Stack Frame

will revert to that time stamp.

Locals Pane

All arguments and local variables will be displayed here. If

the program has been compiled without the -g flag, local variable names

will displayed as var1, etc.

'this' Pane

This pane displays the current 'this' object (or the class object for

static methods).

Trace Pane

For each thread, this shows the trace of all method calls

that were made. Only three arguments are shown. Only ten are recorded.

Code Pane

This displays the current line of code. The buttons all move

forwards or backwards starting from this line. The two exceptions are:

when a higher stack frame has been selected (see Stack Pane) and when a

time stamp occurs in a source file that can't be found, in which case the code pane

will be empty.

I/O Pane

This shows the all the lines written by System.out.println() and System.err.println(). (Obviously,

only calls from instrumented code.) If the line is preceded by "--", that

indicates that the current time is previous to the time that line was

written. (Eventually this pane will show calls to print(), write(), etc.

going to any I/O stream.)

Objects Pane

This shows whatever objects the user has copied here via double-clicking on

objects in other windows. Double-clicking on an instance variable will add

that object to the pane. Double-clicking on an object in this pane will

"close up" that object, hiding all its instance variables. Double-clicking

a second time will open it back up. Individual instance variables may also

be removed selectively (see Objects->Remove and Objects->Retain Only).

Double-clicking on an instance variable will expand the value

of that instance variable in-place (like the array int[20]_0 in

figure 1). If the value is a primitive or is an object with no visible instance

variables, nothing will happen. Pushing the Previous Value button, etc.

will advance to the next value of the instance variable, not the

next value of the instance variable's instance variable. For example, the

previous value of array in figure 1 is null, so

the array will disappear if you go there. If you select an

instance variable's instance variable, the commands will work on that, which

could cause it to disappear if the instance variable also changed value.

(This recursive stuff is a little confusing to explain. Just try it.)

Values which have not yet been

set (e.g., instance variables of objects before they have been created) will

be displayed as "--". Variables which changed values from the previously

selected time stamp will be displayed with a leading "*".

Currently only a single level of recursion is supported. Double-clicking on an

instance variable's instance variable will copy that

instance variable to the top level of the pane. An instance variable's value may also be

copied to the top level via Objects->Add Instance Variable.

The Objects menu allows you to display class object of the selected object (and the static

variables thereof) Objects->Add Class.

Navigation

Navigation has never been a issue in traditional debuggers because there

wasn't much to think about. You pushed Continue, the program resumed

and ran until it hit the next breakpoint, and that was it. We need to be

a bit more formal because there are so many more ways to get from here

to there and back again.

The ODB provides a variety of methods for navigating through the program

run. They are all aimed at making it as simple as possible for the programmer

to get to "interesting" points in the program and see what state it was in.

The ODB implements what I believe are the most "obvious" methods, with plenty

of room for adding others.

The primary modes of navigation are:

o Selecting a line in the trace window, which will revert the debugger to

the time of the first time stamp recorded in that method. If that method

was not instrumented, then the debugger will revert to the line it was

called on.

You may request the debugger to always to the calling line by turning

Trace->Go to first line in method off.

o Selecting a line in the code window, which will revert the debugger to a

time stamp on that line (see below).

o Pushing one of the buttons, which will revert the debugger to a time stamp

depending on the currently selected object or line in that pane. (See Navigation

Buttons below.)

o Selecting a line in the Stack pane, which will not change the current time

stamp, but will show you where methods in the stack were called from

(reverting the code pane) and the values of the local variables. (See Stack Pane.)

o Selecting a thread, which will revert to the nearest time stamp in that

thread, earlier than the current time preferred. (All instrumentation methods

are synchronized, so time stamps are strictly sequential.)

o Selecting a line in the I/O window, which will revert to the time when the

newly selected line was printed.

The choice of which time stamp on a line in the code pane to select may be

controlled by a set of options in the Code menu. The normal direction is to

go backwards in time if the newly selected line is above the previously

selected line, and forwards if not. Going forwards, you will select the

first TS (of a contiguous set, e.g., call/return) on a line, going

backwards, you will select the last. Normally the time stamp has to be in

the current thread. You may also restrict the choice to being in the same

method call. (The best behavior here is hard to determine. I've played with

lots of ideas.)

Navigation Buttons

The buttons work as uniformly as possible for the different panes. The four

arrow buttons revert to the first, previous, next, and last time for

selected object in that pane. All of the buttons have tooltip messages.

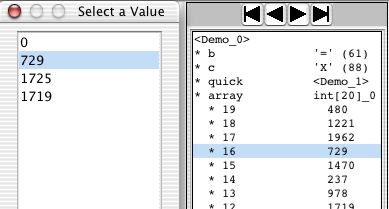

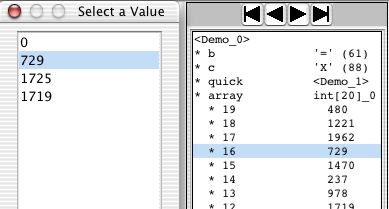

You may bring up a list of all the values a variable ever had and

select one of them. The commands Object->Select IV Value selects a value

for an instance variable, and Object->Select Local Value

selects a value from a local variable. The ODB will revert to the time

when that variable first took that value.

Now for the Details

If you are just starting, skip down to "Installing the Debugger" and spend some

time playing with the demo.

Minibuffer

Modeled after EMACS, extended commands (such as Evaluate Expression and

Search) are displayed here, as are messages to the programmer.

Searches

You may do an incremental text search through

the trace pane. <Ctrl-S> will start the search and give focus to the

minibuffer. Typing characters will extend the search string. Another

<Ctrl-S> will advance to the next match. <Ctrl-R> will reverse the search.

<Return> will end the search. <Ctrl-G> will abort any command.

The search is case-insensitive and looks for two things: the exact characters

on the screen (including the ".." for very long names), and the characters

in the individual objects (i.e., the complete name for long names and

strings). TABs are typed as themselves (not <Ctrl-I>, not "\t"), newline

characters are entered as "\n". In the middle of a search, double-clicking

on an object will add that object to the search string.

"Event" searches are provide via the "Fget" commands (<Ctrl-F>). They are

executed as incremental searches based on the pattern typed in (another

<Ctrl-F> will find the next match and <Ctrl-R>

will search in the reverse direction). A typical pattern would be (note the

"Prolog style"):

port = call & to = THIS & arg0 = <MyObj_5>

which will search for method calls ("port = call") whose

"this" object ("to = THIS") will be assigned to the variable

THIS (NB: a sybmol in uppercase means it's a variable) and whose first argument

("arg0") is <MyObj_5>.

Port must be one of: call, return, enter (first line in a

method), exit (last line in a method), civ

(change instance variable), clv (change local variable),

chgArray (change array element).

o All ports define "to" (this object), "toc" (this object

class), "mn" (method name), "thr" (thread), and "pN" (parameter 0-9).

o "Calls" also define "argN" (argument 0-9) and "cmn" (call method name).

o "Returns" define "rv" (return value).

o "Changes" define "nv" (new value).

Strings are entered with '"' and class objects are prefixed with

a '#'. All objects may be compared with '=' and '!='.

Integer values may be compared with '>' and '<'.

Hence this pattern:

port = enter & mn = "sort" & toc = #fr.insa.Thing & p0 > 3

will match the first line in any method named "sort" in the

class fr.insa.Thing whose first parameter is an int greater

than 3.

There are two commands on the Trace menu which will create queries

for you, matching either the current trace line (i.e., the current method

call) or the current source line. These will be stored as the

"previous" FGET query so that typing <Ctrl-F><Ctrl-F> will show them.

Typing <Ctrl-T> in the midst of an FGET query will display the total

number of matches in the entire run of the program (starting with the

currently selected time).

Marking Points of Interest

The ODB maintains a ring of "marks" for time stamps. You may add a mark to the

ring with <Ctrl-SPACE>. You may then revert to that mark with <Ctrl-X>. The

ring is circular, and if there is more than one mark, <Ctrl-X> will cycle through

the ring.

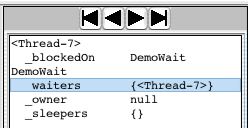

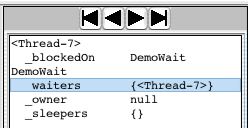

Locks and Wait Sets

When a thread blocks, waiting for a lock or calls wait() , the object on which it

blocks will be displayed next to it in the Threads Pane (e.g.,

<Thread-7>

is blocked on the class object DemoWait

below). A pseudo-instance variable _blockedOn

will be added to the thread and shown in the object pane if the thread is

displayed there. Three pseudo-instance variable ( _waiters, _owner,

_sleepers) will be added to the object. If a thread blocks in

uninstrumented code, the ODB will not notice.

Filters

If you have a large number of trace lines which are not particularly

interesting, you may filter them out using the Filter menu options. You may

filter out individual methods (hiding them and their internals), filter out

method calls deeper than some limit, or filter in one method (hiding

everything else). And you may "unfilter" everything. You may save the

filters to the .debuggerDefaults file (see options) and the next time you

instrument those classes, those methods will neither be instrumented nor

recorded.

Probably the most useful filter option is to "filter in" a method, hiding

all method calls outside of the selected one.

All panes reflect the current time stamp (except when navigating using the

stack). The code lines are those defined by the compiler, so there may be

many time stamps on one line of code. Each method call generates two time

stamps -- one for the call, one for the return. If it's instrumented, the

method then also records the first line executed and the last line. If

return is not called directly, the Sun compiler assigns the implicit return instruction

to the first line of the method (kinda weird). This line:

t = first(tl.getNext());

generates five time stamps, two calls, two returns, and an assignment. Logic,

flow of control,

and operators generate no time stamps. This:

if ( ((a + 71) > (b * c)) || (this == that) ) break;

generates no time stamps.

Evaluating Expressions Interactively

Arbitrary method calls may be made at any time. You may revert the debugger

to any time you wish and then evaluate a method call using the current

values of the recorded objects. So if you revert to time 1234, when

<Demo_0>.array elements 16 and 17 are 454 and 123 respectively, calling

<Demo_0>.quick(16, 17) will sort those two. If you advance to time 1330,

when 16 and 17 are already 123 and 454, then sorting them won't change

anything.

In order to maintain some sense of consistancy, the methods will be executed

in a different "timeline". Basically, the current state will be copied into

a new timeline which is initialized with only one time stamp. The method

will then be run (with recording turned on and off automatically),

populating this new timeline. You can switch back and forth between the two

timelines freely. Further method calls will clear the secondary timeline

before running.

In the secondary timeline you may change the value of instance variables

before running. The commands are all on the main menus, with keyboard

accelerators. <Tab> will do an auto-complete on object and method

names. <Return> will execute the command (running the method or setting the

instance variable value).

These commands are the least robust part of the debugger. The interactive

"Evaluate Expression" only accepts four arguments. The arguments must be

object or class print strings (e.g., Demo, <Demo_0>), strings, integers,

true, false, or null. You cannot change the value of final variables. One

space is required after each "," and nowhere else. <Return> and <Tab> must

be typed at the end of the minibuffer. You can only change the values of

variables of type Object, int, and boolean. Lock states and wait sets cannot be

set, so their displays will be set to "unlocked" and "empty".

Garbage Collection

There is a limit to the number of time stamps that can be recorded. Each

simple time stamp takes three words (12 bytes on a 32-bit system) and each

method call/return takes about 25 words and another 25 for the JList to display

it.

And then your program probably needs to use some memory also.

The ODB looks at the value of the MEMORY environment variable (or

MaxTimeStamps in .debuggerDefaults) to determine

how much memory to devote to time stamps. Currently it allows a maximum

of MEMORY/200 time stamps. (You'll notice that the aliases default to

400MB, allowing 2m time stamps.) When that number is exceeded, the

ODB's "garbage collector" kicks in and throws away some of the early time

stamps.

The defaults are set on the command line by the aliases such as

this one (for debug):

java -Xms400100100 -Xmx400100100 -DMEMORY=400100100 -cp $HOME/Debugger/debugger.jar:$CLASSPATH $USER_FLAGS com.lambda.Debugger.Debugger

The flag -Xmx sets the maximum memory for the program, -Xms

sets the initial memory size. We want to avoid useless early JVM garbage collections,

so they are set to the same size. Depending on your program, you may wish to

increase these numbers while keeping the value of MEMORY low. This would give

your program more room of its own.

Of course these are not really garbage. So the ODB attempts to retain the

time stamps which are most likely to be interesting (object changes), while throwing away

those that aren't. In the first mode, the ODB throws away all time stamps

for local variables and method calls that are older than 50% of the entries.

If this is insufficent (less than 10% are collected), then the second mode

kicks in and entries for objects are also collected.

On each invocation, the collector will print out a line similar to this:

ODB: Collected 244783 out of 326382 stamps and 47268 TraceLines

Although very clever, it is not clear that the GC is actually useful. If you turn it

off, collection will simply stop when storage is filled up. (See the environment variable GC_OFF.)

Objective of the ODB

I originally wrote a paper describing this so that someone else would write

a proper debugger/IDE so that I could use it. Then I thought it would be

good if I could prove that this was actually useful. So I wrote a little

mock-up, which evolved into this full-fledged proof-of-concept. I claim that

the ODB is sufficient proof that the idea of "omniscient debugging" works

and works very well.

So, there are lots of guesses about what data would be most useful, how it

should be displayed, what navigation commands make sense, etc. Most of the

surrounding pieces of an IDE have already been done quite well by other

folks. So, for compilation, editing, class browsing, etc. I simply assume

that the ODB will be properly integrated into those bits which work best.

I wrote the ODB in Java because it was easy. Omniscient Debugging

could equally well be applied to C, C++, Eifel, etc.

Optimizations and Limitations

Other than any exceptions noted in the "bugs" section below,

the ODB shows data which is 100% correct and can be

confidently run on any Java 1.3 1.4, or 1.5 program. (ODB1.4 for

SDK 1.3 and 1.4, and ODB1.5 for SDK1.5.)

Unless there are bugs I don't know of (ha-ha).

If you don't need to get fancy, stop now. You'll probably never use the

stuff below.

Although it is possible to record absolutely everything, it is rather

expensive and not very useful. For classes which are trusted (such as the

JCF classes, library classes, and your own well-tested classes), it is

possible not to instrument them. Indeed, the default is to instrument and

record only those classes in the package of the main method. The debugged code will

run faster and the debugger will not be cluttered with uninteresting

data. There are some limitations...

The limitations include: any direct changes to an instance variable (e.g.,

obj.iv = value;) performed in non-instrumented code will not be recorded

(it's bad OOP practice to set instance variables directly anyway! You should be

using getters and setters.), calls from non-instrumented code (e.g., from

the event loop) back into instrumented code will look funny (the call chain

won't be visible. These "unparented" calls are marked in the trace pane with

"**" preceding the call.), calls to System.exit() in non-instrumented code

will exit the process.

You may clear the history and record new data from a live application (e.g.,

when debugging a button push), or restart the same. You may select a line in

the program and tell the debugger to turn recording on/off there. You may

select a line of output for the same purpose.

Objects which were created outside of instrumented code will not be

recognized until they are touched in instrumented code. The

actual creation time is thus not known and their instance variable values

will not be known. They will be marked with a "@" in the Objects Pane.

Some classes are just crying out for special, hand instrumentation. Vectors,

for example, really want to be displayed as if they were arrays which just

happen to be of the exact right size. This is done by replacing Vector with

MyVector during instrumentation.

Obviously, instrumenting classes which the ODB uses (e.g., Swing)

will not work. If you are working on such code, you will have to change the

package for the code you're working on. For example, to debug the ODB, a

complete copy of the source tree is made and the package

"com.lambda.Debugger" is replaced by "lambda.Debugger." I do the same thing

when debugging Swing itself.

Displaying very large objects is awkward. By default, objects with more than

1000 instance variables (i.e., arrays) will display only the first 1000, and

print (Objects>Print) only the first 10000.

Options

The ODB normally inserts instrumentation while loading classes via a

subclass of java.lang.ClassLoader.

This is done by default for classes in the package

of the main method. Thus, if you use Apache's crimson package it won't

be instrumented unless you specifically request it (see .debuggerDefaults).

It doesn't matter where the files are loaded from.

Normally the ODB will bring up the main debugger window as soon as the

target program's main thread returns or System.exit() is called from

instrumented code. (The exit() method gets replaced by a call to throw a

DebuggerExit exception.) Any other threads in the program will

be suspended on their next call to instrumented code.

For programs in packages, CLASSPATH must be set correctly (the aliases will

pick this up when they are run), so you must start the debugger from the

command line.

This is also true

for code from jar files--you must put the jar file in the CLASSPATH

and start the debugger from the command line. (Microsoft details are noted below.)

% setenv CLASSPATH /home/your_directory/your_code.jar

% debug com.your_company.CoolProgram arg1 arg2

All of the options below may be selected from the controller window if the

debugger is started with the DONT_START flag (use debugp). Once you figure out

what setting you want, it's more convenient to use the appropriate alias.

For programs that spawn new threads which continue to run after main()

returns (e.g., any windowing program), you should set the DONT_SHOW flag (run

the alias debugn ). Recording will continue until you push the Stop

Recording button.

You may set the PAUSED flag to start the program without starting recording.

For example, when there's a bug when pushing a button, you can setup the windows

without recording.

You may set both

flags from the command line or the controller window, allowing you to start, stop, and

restart recording. You may see some odd looking traces if the program is not

quiescent when you start and stop it.

You may request that certain methods not be instrumented or not be recorded,

by placing their class and method names into the .debuggerDefaults file in the current

directory.

For example, StringBuffer and StringWriter aren't be recorded by

default, thus ridding the trace pane of lines from code like this:

"Teach "+ n +"dogs new tricks!"

(which actually involves a new

StringBuffer, two appends, and a valueOf()

call). The methods not instrumented by default are: toString() and

valueOf(). Those not

recorded are: toString(), valueOf(),

and <cinit> (Class

constructors -- "initialize statics") and all StringBuffer

methods.

If you really want to record/instrument everything (hint: you don't!), you

may remove them from the defaults file. You may use the Filter menu to add methods

to it or edit it by hand (see Defaults File below).

You may instrument specific classes in different directories by hand:

% debugify MyObject1.class MyObject2.class ...

If you want to run the debugger and have it not instrument any files, you

may pass the DONT_INSTRUMENT flag. (Presumably you have

debugified some files by hand.) This may be done with the alias/bat file:

% debugdi MyProgram arg0 arg1...

If you start the debugger with no arguments or from a file manager, a file

chooser will pop up and allow you to select a program and set these options.

This method is rather limited. The program in question must be in the default

package.

Microsoft Windows

Everything works the same way as above, except that instead of aliases,

batch files are used. It is assumed that you will put the debugger in the

directory c:\Debugger and that you will unpack the batch files

instead of the aliases. Include

them in your path and you'll be ready to go! If you choose a different location,

edit the batch files appropriately.

% jar xf debugger.jar Microsoft

Defaults and the .debuggerDefaults File

Most of the flags and parameters which the ODB uses are defined in a single

file, .debuggerDefaults. This file is located in the current

working directory. If no such file is found when the ODB is started, it will

create one. After that, the ODB will not change the file unless you specifically

request it to. You may edit the file by hand and the ODB will retain your changes.

(Thus you may run the debugger once and then edit the file it writes out.)

You may declare a class which you write to be the "special" format for

displaying objects of some type (typically classes, but primitives are

allowable). Look at the example in the source for SpecialTimeStampFormatter.java.

These would be listed as:

SpecialFormatter: com.lambda.Debugger.SpecialTimeStampFormatter

and would be so displayed only in the Objects window when you select the

object (or an array of such objects) and execute Objects>Special Format.

Here is a sample. All of the lines may have duplicate entires (e.g., the

DontInstrumentMethod lines below), except for the start/stop lines.

It is unlikely you will change anything other than "*Instrument/Record*"

and "UserSelectedField" by hand.

# ODB Defaults -- You may edit by hand. See Manual for details

MaxTimeStamps: 400000

StartPattern:

StopPattern:

SourceDirectory:

OnlyInstrument: "org.apache"

OnlyInstrument: "fr.emn.info.eaop.cps"

DontInstrument: "recoder.java.declaration.TypeDeclaration"

DontInstrumentMethod: "* toString"

DontInstrumentMethod: "* valueOf"

DontRecordMethod:

DontRecordMethod: "* toString"

DontRecordMethod: "* valueOf"

DontRecordMethod: "java.lang.StringBuffer *"

DontRecordMethod: "java.lang.Object new"

UserSelectedField: "com.lambda.test.MyClass name"

You may request some objects to include a field value in

their print string by setting the user selected field as

above. The field choosen must be a primitive and must not

change.

The ODB will write out a "DidntInstrument/OnlyInstrument" line for every single

class loaded. This makes it easier to change the set of classes being

instrumented. By default, only the classes in the package of the

"main" method are instrumented.

Finding the Source Code

The ODB will look for source code in the same directory it loaded the class

files from. If there is no java file there, the ODB will then look in the

current directory. If it doesn't find anything there, it will popup a file

chooser so you can tell it where the source is.

Any directories you add will be written into the defaults file

in the current directory and loaded on subsequent runs.

Known Bugs

The "Heisenbug Principal" of software (observing a program changes its

behavior) will always apply, but there shouldn't be any particular

differences from running under a traditional debugger. The one exception

is when a program suffers from cache incoherency. If you fail to properly

lock a shared variable, it is possible for CPU 1 to write a value to

that variable and for CPU 2 not to see that new value for some

time. The ODB will prevent this bug from occuring. There are static

lock analyzers. Use one. The substitute collection classes (MyArrayList,

Vector, Hashtable) don't record changing entries via enumerators.

The clock displayed on the menu bar is of very doubious value.

Java puts a "catch" around all code that uses locks. Normally you don't

notice this. It will appear as an "extra" catch in the ODB.

Calls to "super" methods will look like calls to static methods. (It's

not clear what kind of display would be the most "intutive".)

<MySubObj_4>.frob() -> void

MySuperObj.frob() -> void

frob -> void

Some char and

boolean values are recorded as int.

A few Swing bugs and error messages appear in JDK

1.3, which you can ignore (pressing "Stop" in the controller again will

force redisplay -- useful in JDK 1.3). Arrays only display the first 1,000 elements. The I/O pane

only displays calls to println() writing to standard output.

For faster startup on larger projects (100+ files) where most

of the files don't get recompiled very often, you may

instrument your files by hand.

RMI and Serialization Problems

If you serialize an object, the program which unserializes it expects

to have the same class definition as the program which serialized it.

However, if one of the two programs is instrumented and the other isn't,

then you can get a variety of exceptions, such as below. One solution is

to instrument the files directly and simply run one side with collection

turned off.

java.lang.LinkageError: duplicate class definition: ClientImpl_Skel

Possible Verifier Bugs

Because the ODB works by instrumenting the class code, it is

possible that your javac compiler produces code in a form

that the debugifier won't work with. (It works with all the

code I've produced, but I have been surprised before.) The

only thing you can do is to: (a) put that class in the "don't

instrument" list, or (b) debugify all the other files by hand

and run the ODB with instrumentation turned off. And report

the bug to me.

A typical verifier error (and related linker error) looks like this:

java.lang.VerifyError: (class: BadClass, method: bar signature: ()V)

Unable to pop operand off an empty stack

java.lang.LinkageError: Class org/xml/sax/EntityResolver violates loader constraints

Classloader Issues

The default operation of the ODB is to use a classloader I wrote, which

is a simple subclass of java.lang.ClassLoader. However, if you use your

own classloader for some of your code, then that code won't be instrumented and

it might even cause a classloader conflict (classes mine loads won't recognize

classes yours loads). Methods that depend on a specific classloader will also

fail. The method Class.getPackage() for example, accesses the classloader

to determine the package (for some reason). It will return null for my classloader.

You may either instrument by hand (above) or

build and install a system classloader:

java com.lambda.Debugger.InstrumentorForCL ~/Debugger

or

java com.lambda.Debugger.InstrumentorForCL \Debugger

Future Enhancements

One may imagine all sorts of things. High on the list are: The ability to

change

command line arguments, some more elaborate data display options, saving a

debugging session to disk, integration with IDEs, dynamic reloading of

recompiled code, hand instrumentation of collections,

new navigation commands, a pane to display all I/O, another to display windows,

and of course, performance optimizations. Suggestions welcome.

Performance

This is an unoptimized proof-of-concept implementation. I know of an obvious

order of magnitude improvement in both time and space for the ODB. Other

implementations could do even better. So what can you expect? It works fine

for me when debugging the debugger on my 110MHz, 128MB SS4. On my SS4 with a

80MB maximum heap size, I can reasonably create and navigate

40,000 "typical" method calls (with 10 time stamps inside). When you exceed the

amount of physical memory available, performance will degrade somewhat.

The ODB does run fairly well even in very large virtual spaces -- until you

have to garbage collect. Your program may not.

It is possible for a program to create far more time stamps than the ODB can record. You can

certainly expand the maximum heap up to the 31-bit limit (2GB). I have successfully

collected 100 million time stamps and been able to navigate through them, but it's

clearly slower than I'd like.

It is highly

unlikely that collecting so many time stamps will be useful, simply because

it is so difficult to find your way through that much data. Selective

instrumentation, judicious use of Start and Stop, and intelligent narrowing

of the code to the bug will almost certainly be sufficent.

Installing the Debugger

Download the jar file (on: www.LambdaCS.com/debugger/debugger.html)

into $HOME/Debugger, then

extract the aliases (see above for .BAT files). Define the latter.

If you wish to add command line properties (e.g.,

-DYOUR_PROPERTY) you can set the variable USER_FLAGS.

The aliases (debug, debugn, debugp) will now work.

% cd ~/Debugger

% jar xf debugger.jar aliases

% source aliases

% setenv USER_FLAGS -DYOUR_PROPERTY

% debug YourProgram

or

% cd \Debugger

% jar xf debugger.jar Microsoft

Place the files Microsoft/*.BAT where you will find them.

% set USER_FLAGS=-DYOUR_PROPERTY

% debug YourProgram

Running the Demo

Start the ODB by double-clicking. Select "Demo" (a multithreaded quicksort) from

the file chooser. It will run, the debugger will popup, and you will be able

to "explore" the program.

Bil Lewis

29 December 2006